A kidney stone forms within the renal pelvis and calyx (calyces, pl.) and eventually try to pass through the ureter, into the bladder and out through the urethra. The pain comes if the stone is stuck and urine pressure builds behind the stone.

A kidney stone forms in the pyelocalyceal system within the kidney. When a stone “passes” it moves from the pyelocalyceal system and into the ureter, the narrowest part of the collecting system. The stone often gets stuck within the ureter causing obstruction. The severe pain of a kidney stone comes from the obstruction of the urine, not from the size, location, composition, or shape of the stone.

When a stone passes, the recommendations for treatment depend on the size of the stone and where the stone is located.

Treatment Options Include:

Letting the Stone pass on its own: Drinking plenty of water and other liquids while passing a stone can help flush out smaller stones and prevent infection from settling in behind larger stones. Drinking enough fluid while passing a stone can be difficult given the nausea associated with passing a kidney stone. Over-the-counter or prescription pain medications can help manage the pain while the stone passes. Controlling pain during a stone passage episode is critical to keep patients out of the Emergency Room. Many stones will pass on their own if given enough time. Often the critical issue for stone passage is the control of pain.

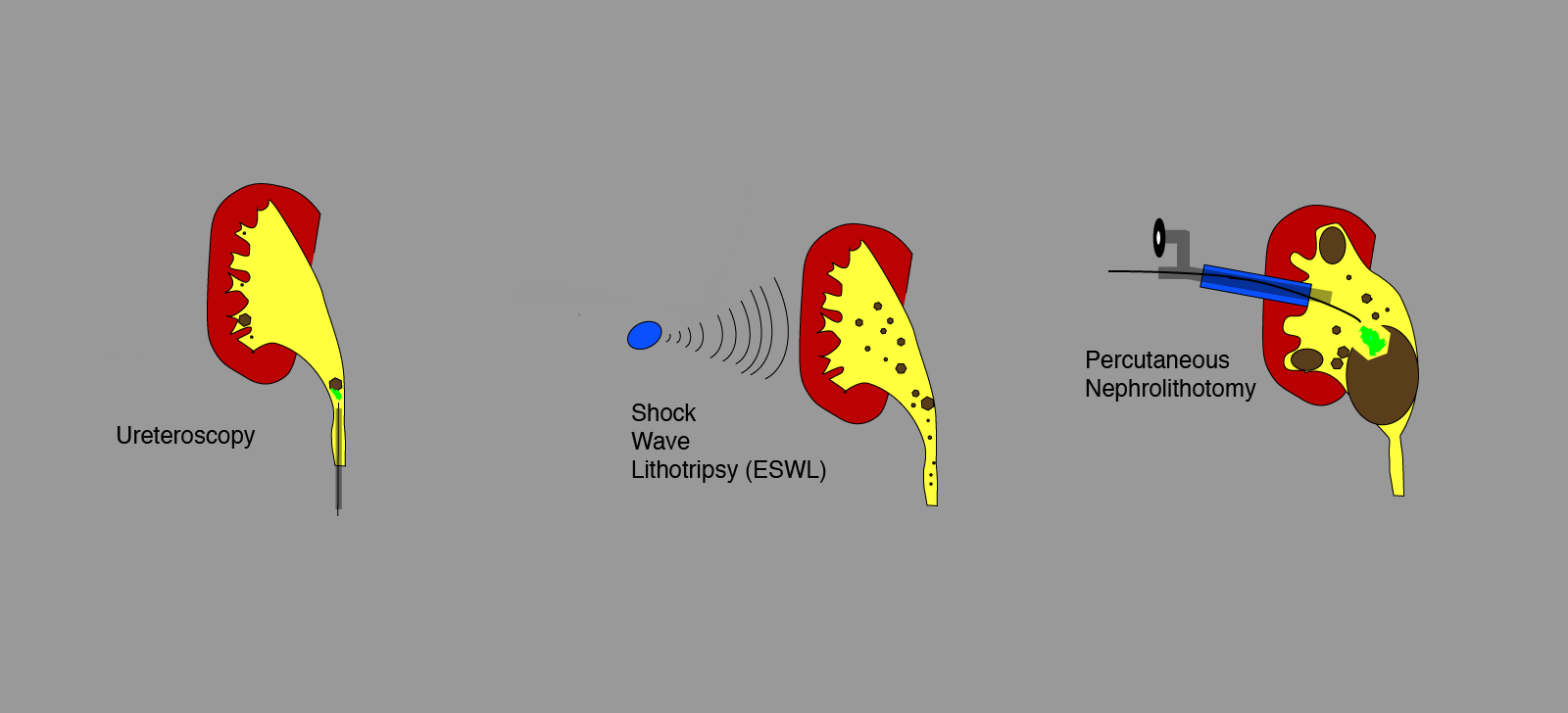

Surgical Procedures: For larger stones that cannot pass or smaller stones that refuse to, surgical procedures such as ureteral stent or nephrostomy tube, ureteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy may be necessary to remove the stone. The choice of which procedure and when to perform it requires a consultation and discussion with your provider. The downloadable PDF goes into greater detail the procedures listed here as well as the risks involved with the various procedures.

Kidney stones come in a variety of sizes and locations within the urinary tract. Choosing the appropriate management for your stone is very important. Stones that can pass on their own should be left alone to pass spontaneously. Options for treatment include anything from an observation protocol and monitoring for smaller stones up to large incisions and removal of kidney for the most extreme and uncommon cases. Stones that are too large to pass or possibly causing infection, severe pain, or hospitalization need to be treated with surgical removal. The most common procedure performed is a ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy and stone removal.

Listed below are the options available for treating stones in 2024. You can download the PDF explaining the all procedures in greater detail in the link below.

1. Conservative (passing a stone on your own): Small stones will often pass on their own. Drink lots of fluids, take pain medication as needed. Time and pain tolerance are the critical factors in allowing a stone to pass on its own.

2. Stenting or Percutaneous Nephrostomy: Sometimes a drain needs to be placed to drain the kidneys on a temporary basis. These are not permanent tubes, but rather a way to make sure a kidney has adequate drainage to protect it, or in cases of infection to allow an infection to drain. A stent is placed in the ureter. It is entirely internal, spanning from the kidney to the bladder. A percutaneous nephrostomy is placed through the skin directly into the kidney through the back and drains to a bag.

3. ESWL: Some stones can be broken up by passing shock waves through the skin focused on the stone. The fragmented stone particles will then pass on their own.

4. Ureteroscopy: This is the most common procedure that is performed. Here a small scope is passed into the bladder through the urethra and up the ureter to the kidney where the stone be caught and removed intact or broken up into small pieces most commonly with a laser. A broken stone can be removed through basket extraction, irrigated from the kidney, or broken up into small enough particles the stone fragments will pass without notice down through the ureter.

5. Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: For the largest of stone a small incision is made in the back and a tract to the kidney is dilated a scope can be passed into the kidney. Through the scope instrumentation can break up a large stone to allow it to be removed in pieces.

6. Open or Laparoscopic Surgery: Rarely do kidney stones do enough damage to require kidney removal or to make a larger incision necessary. Most often an open procedure is used to remove a kidney damaged by infection and very large stones.

Your physician will help you make the appropriate choice for your individual stone.